Subscribe to blog updates via email »

Summary: Old Masters and Young Geniuses, by David W. Galenson – Love Your Work, Episode 288

The book, Old Masters and Young Geniuses shows there are two types of creators: experimental, and conceptual. Experimental and conceptual creators differ in their approaches to their work, and follow two distinct career paths. Experimental creators grow to become old masters. Conceptual creators shine as young geniuses.

The book, Old Masters and Young Geniuses shows there are two types of creators: experimental, and conceptual. Experimental and conceptual creators differ in their approaches to their work, and follow two distinct career paths. Experimental creators grow to become old masters. Conceptual creators shine as young geniuses.

Listen to the Podcast

- Listen in iTunes >>

- Download as an MP3 by right-clicking here and choosing “save as.”

- RSS feed for Love Your Work

University of Chicago economist, and author of Old Masters and Young Geniuses, David Galenson – who I interviewed on episode 105 – wanted to know how the ages of artists affected the prices of their paintings. He isolated the ages of artists from other factors that affect price, such as canvas size, sale date, and support type (whether it’s on canvas, paper, or other).

WANT TO WRITE A BOOK?

Download your FREE copy of How to Write a Book »

(for a limited time)

He expected to find a neat effect, such as “paintings from younger/older artists sell for more.” But instead, he found two distinct patterns: Some artists’ paintings from their younger years sold for more. Other artists’ paintings from their older years sold for more. He then found this same pattern in the historical significance of artists’ work: The rate at which paintings were included in art history books or retrospective exhibitions – both indicators of significance – peaked at the same ages as the values of paintings.

When he looked closely at how painters who followed these two trajectories differed, he found that the ones who peaked early took a conceptual approach, while those who peaked late took an experimental approach.

Cézanne vs. Picasso

The perfect examples of contrasting experimental and conceptual painters are Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. Paintings from Cézanne’s final year of life, when he was sixty-seven, are his most valuable. Paintings from early in Picasso’s career, when he was twenty-six, are his most valuable. A painting done when Picasso was twenty-six is worth four times as much as one done when he was sixty-seven (he lived to be ninety-one, and his biographer and friend called the dearth of his influential work later in life “a sad end”). A painting done when Cézanne was sixty-seven – the year he died – is worth fifteen times as much as one done when he was twenty-six.

Le Jardinier Vallier, Paul Cézanne’s final painting, from his most influential, final year.

Cézanne, the experimenter

Cézanne took an experimental approach to painting, which explains why it took so long for his career to peak. Picasso took a conceptual approach, which explains why he peaked early.

Cézanne left the conceptual debates of Paris cafés to live in the south of France, in his thirties. He spent the next three decades struggling to paint what he truly saw in landscapes. He felt limited by the fact that, as he was looking at a canvas, he could only paint the memory of what he had just seen.

He did few preparatory sketches early in his career, but grew to paint straight from nature. He treated his paintings as process work, and seemed to have no use for them when he was finished: He only signed about ten percent of his paintings, and sometimes threw them into bushes or left them in fields.

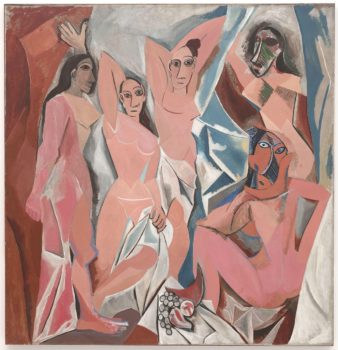

Les Demoiselles d’Avignion, Pablo Picasso’s most-influential painting, done at age 26.

Picasso, the conceptual genius

Picasso, instead, executed one concept after another. He had early success with his Blue period and Rose period, then dove into Cubism. He often planned paintings carefully, in advance: He did more than four-hundred studies for his most valuable and influential painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. One model described how he simply stared at her for an hour, apparently planning a series of paintings in his head, which he began painting the next day, without her assistance.

Cézanne said, “I seek in painting.” Picasso said, “I don’t seek; I find.” Cézanne struggled to paint what he saw, and Picasso said, “I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.”

Experimental vs. conceptual artists

Here are some qualities that differ between experimental and conceptual artists:

- Experimental artists work inductively. Through the process of creation, they arrive at their solution.

- Conceptual artists work deductively. They begin with a solution in mind, then work towards it.

- Experimental artists have vague goals. They’re not quite sure what they’re seeking.

- Conceptual artists have specific goals. They already have an idea in their head they’re trying to execute.

- Experimental artists are full of doubt. Since they don’t already have the solution, and aren’t sure what they’re looking for, they rarely feel they’ve succeeded.

- Conceptual artists are confident. They know what they’re after, so once they’ve achieved it, they’re done, and can move on to the next thing.

- Experimental artists repeat themselves. They might paint the same subject over and over, tweaking their approach.

- Conceptual artists change quickly. They’ll move from subject to subject, style to style, concept to concept.

- Experimental artists do it themselves. They’re discovering throughout the process, so they rarely use assistants.

- Conceptual artists delegate. They just need their concept executed, so someone else can often do the work.

- Experimental artists discover. Over the years, they build up knowledge in a field, to invent new approaches.

- Conceptual artists steal. To a greater degree than experimental artists, they take what others have developed and make it their own.

Other experimental & conceptual artists

Some other experimental artists:

- Georgia O’Keeffe: She painted pictures of a door of her house in New Mexico more than twenty times. She liked to start off painting a subject realistically, then, through repetition, make it more abstract.

- Jackson Pollock: He said he needed to drip paint on a canvas from all four sides, what he called a “‘get acquainted’ period,” before he knew what he was painting.

- Leonardo da Vinci: He was constantly jumping from project to project, rarely finishing. He incorporated his slowly-accrued knowledge of anatomy, optics, and geology into his paintings.

Some conceptual artists:

- Georges Seurat: He had his pointillism method down to a science. He planned out his most-famous painting, Sunday Afternoon, through more than fifty studies, and could paint tiny dots on the giant canvas without stepping back to see how it looked.

- Andy Warhol: Used assistants heavily, saying, “I think somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me,” and “Why do people think artists are special? It’s just another job.”

- Raphael: Who had a huge workshop of as many as fifty assistants, innovated by allowing a printmaker to make and sell copies of his work, and synthesized the hard-won methods of Leonardo and Michelangelo into his well-planned designs.

Experimental & conceptual creators in other fields

Galenson has found these two distinct experimental and conceptual trajectories in a variety of fields. This runs counter to the findings of Dean Simonton, who believes the complexity of a given field determines when a creator peaks. Galenson argues that the complexity of having an impact in a field changes, as innovations are made or integrated into the state of the art.

Sculpture

In sculpture, Méret Oppenheim had a conversation in a café with Picasso, and got the idea to line a teacup with fur. It became the quintessential surrealist sculpture, Luncheon in Fur, but it was totally conceptual. She continued to make art into her seventies, and never did another significant work.

Méret Oppenheim’s Luncheon in Fur was her one significant contribution to sculpture, made at 23.

Constantin Brancusi spent a lifetime as an experimental sculptor. He said, “I don’t work from sketches, I take the chisel and hammer and go right ahead.” He did his most famous work, Bird in Space, when he was fifty-two.

Constantin Brancusi experimented for decades to arrive at the forms of Bird in Space.

Novels

In novels, Mark Twain wrote The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn experimentally, in at least three separate phases, over the course of nine years. He finally published it when he was fifty. Hemingway’s novels were conceptually driven, using his trademark dialog as one of his major devices. He picked up this technique and synthesized it from studying the work of Gertrude Stein, Sherwood Anderson, and Twain himself.

When I talked to Galenson on episode 105, he explained the way to spot the difference between an experimental and a conceptual novel is to ask, “are the characters believable?” Conceptual novelists focus on plot, while experimental novelists focus on character.

Poetry

In poetry, Robert Frost, who spent his career trying to perfect how rhythms and stress patterns affected the meanings of words – so-called “sentence sounds” – wrote “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” when he was forty-eight.

Ezra Pound developed his technique of “imagism” when he was twenty-eight, and had thought it through so well he published a set of formal rules. With this conceptual approach, he created the bulk of his influential poems before he was forty, despite living well into his eighties.

Movies

In film, Orson Welles created Citizen Kane when he was only twenty-six. The carefully-planned conceptual innovations in cinematography and musical score make it widely-regarded as the most influential film ever.

Alfred Hitchcock didn’t make his most-influential films until the final years of his life, as he was about sixty. He said, “style in directing develops slowly and naturally.”

Are you an old master, or young genius?

I really enjoyed Old Masters and Young Geniuses. I find this dichotomy of experimental versus conceptual approaches really helpful in understanding why, in general, some creative solutions come quickly, while others take months or years of searching.

Do you have a choice in the matter?

Galenson is careful to stress that you aren’t either an experimental or conceptual creator – it’s a spectrum, not a binary designation. But in case you’re wondering if you can make yourself a conceptual creator, to become successful more quickly, Galenson says you can’t. You might switch from a conceptual to an experimental approach, and find it works better for you, as did Cézanne, or you might try to go from experimental to conceptual and find it doesn’t, as did Pissarro. But you can’t change the way you think. He told me, “It’s like trying to change your brain, and we don’t know how to do that.”

Join the Patreon for (new) bonus content!

I've been adding lots of new content to Patreon. Join the Patreon »

Subscribe to Love Your Work

Listen to the Podcast

- Listen in iTunes >>

- Download as an MP3 by right-clicking here and choosing “save as.”

- RSS feed for Love Your Work

Theme music: Dorena “At Sea”, from the album About Everything And More. By Arrangement with Deep Elm Records. Listen on Spotify »