Subscribe to blog updates via email »

Clock Time Event Time – Love Your Work, Episode 235

Before I moved to Colombia, I lived several “mini lives” in Medellín. I came and lived here for a few months. I escaped the very worst portion of the Chicago winters.

WANT TO WRITE A BOOK?

Download your FREE copy of How to Write a Book »

(for a limited time)

There was a phenomenon I experienced every time I came here, which taught me a lot about how I think about time. It always happened right around the three week mark.

Getting used to a slower pace of life

The pace of life in Medellín is different from the pace of life in Chicago. It’s slower. People talk slower, people walk slower. That thing where you stand on the right side of the escalator so people can pass on the left — yeah, people don’t really do that here. They stand wherever they like. It’s usually not a problem. It’s rare that anyone climbs up the escalator while it’s moving, anyway.

Whenever I came on a trip to Medellín, the same thing happened: The first week, the slower pace of life was refreshing. The second week, as I was trying to get into a routine, it started to get annoying. The third week, some incident would occur, and I would — I’m not proud to say — lose my shit.

A comedy of errors

The last time I went through this transition, it was a concert malfunction. I showed up to the theater to see a concert, and the gates were locked. A chulito wrapper rolled by in the wind, like a tumbleweed. Nobody was around, except a stray cat.

Is it the wrong day? I confirmed on the website: The concert is today, at this time, at this place. So where is everybody?

As I walked around the building, looking for another entrance, I saw a security guard. He told me the concert was cancelled. Something broken on the ceiling of the theater.

This was especially aggravating because of everything I had gone through to get these tickets. My foreign credit card didn’t work on the ticket website, so I had to go to a physical ticket kiosk. But then the girl working the kiosk said the system was down. So I came back the next day, and the system was also down. No, it wasn’t “still” down — it was just down “again.” So I waited in a nearby chair in the mall for forty-five minutes. Then I finally got my tickets.

And now the concert is cancelled. I go to the ticket booth at the theater to get my money back. But they tell me I can’t do that here — I have to go to a special kiosk, across town. Oh, and I can’t do it today — they won’t be ready to process my refund until tomorrow.

I take the afternoon off to go get my refund. After standing in line for half an hour, they tell me they can’t process my refund on my foreign credit card. I have to fill out a form, which they’ll mail to the home office in Bogotá. I should get my refund within ten days.

I’m always wary that I’m an immigrant living in another country — that sometimes the way they do things in that country makes no sense to me. I never want to come off as the “impatient gringo.” But at this point, I become the impatient gringo. I demand my money back, and recount the whole experience to the clerk. In my perturbed state, my Spanish is even more embarrassingly broken.

I give in, fill out the form, and leave the ticket kiosk — without my money. And I’ve been through this enough times to know what’s coming.

Out on the sidewalk, in an instant, as if a switch were flipped in my brain, I go from steaming with anger, to calm as a clam. Months worth of pent-up tension melts away from the muscles in my neck and back. I feel relaxed — almost high.

Flipping the “temporal switch”

I call this moment the “temporal switch.” I’ve talked to other expats about this phenomenon, and they report something similar. That when you first come to Medellín, it takes awhile to get into the rhythm of life here. But once you’re in that rhythm, you’re more relaxed, more laid back. You’re even happier.

You might wonder what my concert catastrophe has to do with the rhythm of life in Colombia. I might be wrong, but somehow it seems that malfunctions are incredibly common here. It certainly seems so to myself and other expats that live here, and even Colombians agree. (If the concert incident is any support for this theory, I’ll add that I never did get a refund — I ended up calling AMEX to do a chargeback.)

These malfunctions have a symbiotic relationship with the rhythm of life. The internal chatter I experience whenever I make the temporal switch might provide some insight. I’m telling myself, “Things aren’t going to work out the first time you try them. You might as well relax, go with the flow, and enjoy the moment.”

So perhaps everyone is telling themselves that. “Things aren’t going to work out the first time you try them.” That could be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In any case, even if things don’t work out on the first try, don’t worry. It will work out eventually. As the Colombians say, ¡No pasa nada!

Some people are on “clock-time.” Other people are on “event-time.”

The main reason I chose Colombia as a place to double down on writing was that I simply do better writing while I’m here. I think this temporal switch has a lot to do with that.

In his global studies in attitudes about time, social psychologist Robert Levine identified two distinct approaches to time: There’s clock-time, and there’s event-time.

Clock-time people schedule according to the time on the clock. Lunch is at this time, this meeting will end at this time, and the next meeting will begin at this other time.

Event-time people schedule according to events. When I’m hungry, I’ll eat lunch. This meeting will end once we’ve met the objective, and if that doesn’t take all afternoon, we’ll have this other meeting after that one.

Event-time and the “eight-day” week

I went through the temporal switch several times before I knew about these two time orientations. Now that I know about clock-time and event-time, much of the behavior that I found puzzling now makes sense.

There’s no better illustration of event-time than how Colombians view a week. If a Colombian wants to meet with you a week from now, they will say, “en ocho dias” — in eight days.

The first time I heard this, I was incredibly confused. Today is Wednesday, so — ocho dias: next Thursday? I was surprised to learn that the eight-day “week” is the standard here in Colombia, as well as many other event-time countries. If today is Wednesday, eight days from now is also Wednesday.

As a clock-time person, I was initially convinced that this was objectively wrong. Counting on the clock, the meeting will take place more or less exactly seven days from now — seven rotations of the earth.

But if you think about it from an event-time perspective, it’s not wrong at all. Today is an event, which has not yet ended. There will be six additional days — each day its own event — between now and the meeting. The day the meeting takes place is an event in itself. Add that up — one, six, one, — and you’ve got eight days between now and the meeting which takes place a week from now.

This is not the Beatles’ Eight Days a Week. That was a malapropism — said by a chauffeur to illustrate that he was working hard. Instead, this is literally how event-time people see the week. It’s a refreshing thought, really: Today counts.

Both clock-time and event-time have their place

It can come off as politically incorrect to even point out these different attitudes about time. If any of these observations sound judgemental to you, stop and think: Is it because one approach sounds better to you than the other? Well there’s your problem!

Both event-time and clock-time are useful, for different contexts. Researchers Tamar Avnet and Anne-Laure Sellier found that both clock-time and event-time approaches can lead to good outcomes. It depends what you’re trying to accomplish.

If you’re trying to be efficient, clock-time is the way to go. If you’re stacking bricks, Frederick Taylor’s approach to timing movements will get the wall up faster. It’s a clock-time approach.

But if you’re trying to be effective, event-time is the way to go. If you’re trying to think of the perfect gift for your tenth wedding anniversary, getting it right is more important than doing it quickly.

Avnet and Sellier’s study also demonstrated that clock-time and event-time approaches aren’t strictly cultural. Most of us change our approach based upon what we’re trying to accomplish. It’s when we use a clock-time approach, when an event-time approach would be better, that we get ourselves into trouble.

Clock-time is a creativity killer

Think about the things you’ve learned in previous episodes of Love Your Work. Remember from episode 218 that creative work follows four distinct stages. Remember from episode 226 that when Frederick Taylor tried to treat time as a production unit his productivity eventually collapsed.

Consider this study from Stanford. They found that the busier knowledge workers were, the less creative they were. The more they struggled to fit work into the time available, the more they let creativity fall by the wayside.

Remember some of the ways that creative work is not like moving chunks of iron or stacking bricks. Ideas can be worthless, or they can be priceless. Ideas can also arrive in an instant. And when they do arrive, the moment they arrive is often far removed from the work that produced the idea.

When the work you’re doing right now isn’t immediately bringing results, and when those results may come unpredictably — at any time — you can see how working on clock-time is a stressful recipe.

Use time as a guide, not as restriction

So what’s the solution? Should you be a clock-time person, or should you be an event-time person? Obviously, if you can’t do anything on-time, you’re going to have a tough time. You’ll disrespect people by showing up late, you’ll miss deadlines. You’ll end up racing against the clock.

But I prefer to think of time as descriptive, not prescriptive. The minutes and hours on the clock are not little boxes that you need to stuff work into. The minutes and hours on the clock are instead rough measurements for how to allocate your energy.

Time is a useful proxy for measuring and dividing up energy. It’s not a strict template for guiding every action you take.

If you read roughly an hour a day, you’ll read a lot of books. If you meditate roughly fifteen minutes a day, you’ll be more present the rest of your day. If you brainstorm something for five minutes today, the solution will come to you sometime tomorrow.

If instead, you’re trying to finish reading a chapter in the next ten minutes, or you’re trying to come up with the perfect company strategy before the meeting ends at noon, your efforts are just going to backfire. Avnet and Sellier have found that people who depend too much on the clock to dictate their schedules are less present, are less able to savor positive emotions, and are less open to the unpredictable and emerging opportunities that are inherent to creative work.

Pay attention to how you’re scheduling your work. Ask yourself: Am I working according to the clock — trying to fit work into restricted time; or am I working according to events — trying to get it right? If you’re trying to be creative, try to practice less clock-time, and more event-time.

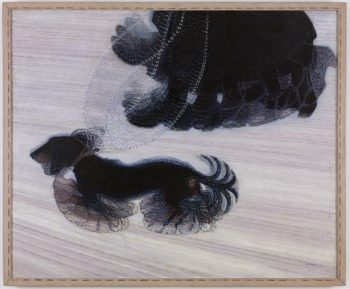

Image: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, Giacomo Balla

My Weekly Newsletter: Love Mondays

Start off each week with a dose of inspiration to help you make it as a creative. Sign up at: kadavy.net/mondays I've been adding lots of new content to Patreon. Join the Patreon »

Join the Patreon for (new) bonus content!

Subscribe to Love Your Work

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Listen to the Podcast

- Listen in iTunes >>

- Download as an MP3 by right-clicking here and choosing “save as.”

- RSS feed for Love Your Work

Theme music: Dorena “At Sea”, from the album About Everything And More. By Arrangement with Deep Elm Records. Listen on Spotify »