Subscribe to blog updates via email »

Leonardo Mind, Raphael World – Love Your Work, Episode 290

The world expects us to be Raphaels, but some of us are Leonardos. Don’t hold your Leonardo mind to Raphael standards, because this Raphael world would be nothing without Leonardo minds.

Listen to the Podcast

WANT TO WRITE A BOOK?

Download your FREE copy of How to Write a Book »

(for a limited time)

- Listen in iTunes >>

- Download as an MP3 by right-clicking here and choosing “save as.”

- RSS feed for Love Your Work

There’s an inscription in the Pantheon in Rome that says, “Here lies that famous Raphael by whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived.” In other words, Raphael was such an amazing painter, Nature was supposedly shaking in her boots, afraid he would learn all her tricks. (Ironically, Raphael’s remains are sealed away in a sarcophagus, where Nature can’t get to them. Who’s afraid of who?)

But Nature had nothing to fear. Raphael could not outdo her. As Raphael was being buried, the painter Nature should have feared lay hundreds of miles to the north, in a little church on the grounds of the King of France’s chateau.

Raphael the young phenom, Leonardo, the old has-been

Several years before Raphael’s early death, he was getting paid thousands of ducats to paint one fresco after another in the Vatican. Meanwhile, the aging Leonardo da Vinci was nearby, living off a meager 33 ducat-a-month stipend, not doing much of importance. The pope had tried hiring him to paint something, but ended up frustrated, saying, “This man will never get anything done!”

When the prolific art patron, Elizabeth Isabella d’Este, who had hounded Leonardo for a portrait for decades, came to visit Rome, she didn’t bother getting in touch with Leonardo. He was a has-been, who couldn’t be counted on to follow through. Who was she there to see? The young phenom, Raphael.

Raphael was very similar to Leonardo, but also very different. His most important difference was that he was a master executor. If you hired Raphael, he got the job done. He also had been raised in the workshop of his father, a court painter for a Duke, so Raphael was refined and well-mannered. He knew how to schmooze with nobility. He had the connections that came along with that background, and could get a letter of recommendation from one powerful person to another with ease.

Leonardo, on the other hand, was born out of wedlock – which made him “illegitimate” at the time – and didn’t get much education. While he had gained a reputation as a brilliant engineer and architect, he had also gained a reputation as an unreliable painter.

Raphael: A reliable Leonardo

As Raphael continued his career as the pope’s wunderkind, Leonardo worked his way north. He left yet another project unfinished in Milan, then impressed King Francis I enough to be invited to join him at the Chateau d’Amboise, as the official painter, architect, and court pageantry designer. While a gig with the King of France wasn’t the worst thing in the world, it was a step down from what Leonardo could have been doing if he hadn’t been reputed as someone who couldn’t get things done. The pope and all the nobles in all the principalities of Italy just watched him go. He’d never return again.

While Raphael had some clear advantages that helped his career advance, he couldn’t have done it without the ways he and Leonardo were similar. The frescoes being painted by the young Raphael – such as his most-famous School of Athens – were exactly the kinds of projects Leonardo would have been great for, if only he could have been counted on to finish them. In fact, there was no person in the world to whom Raphael owed his own painting style more than Leonardo. When it came to painting, Raphael was mostly a reliable Leonardo.

Raphael’s “Leonardo period”

Art historians call the years during which Raphael spent a lot of time in Florence his “Florence period.” But they might as well call them his “Leonardo period.” That’s the four years during which Raphael’s work started looking less like that of his mentor, Perugino, and more like that of his idol, Leonardo.

Young Man with an Apple from early in Raphael’s Florentine period.

Lady with Unicorn from a little later in Raphael’s Florentine period.

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa the three-quarter view of which inspired the above Raphael compositions.

During Raphael’s Florence period, Leonardo was in a public face-off with another young phenom, Michelangelo. Leonardo had been commissioned to paint a battle scene in the Florence Council Hall. As usual, the first deadline came and went. Meanwhile, Michelangelo had done such a great job with his David statue, the council decided it would be a great idea to have him paint a battle scene, too.

It was a pretty awkward situation for Leonardo. He was already struggling to finish, and a committee of which he had been a part had gone against his recommendation for a less-conspicuous location and put the David right outside the entrance of the council hall. Michelangelo was an arrogant prick who openly taunted Leonardo for his past failures, and now Leonardo had to walk through the shadow of Michelangelo’s latest triumph to get to his mural. Oh, and Michelangelo’s battle scene mural was directly across the room from his.

By all accounts at the time, this was a painting competition – a battle of battle scenes. Leonardo wasn’t competitive by nature, but this was supposedly going to motivate him to finish his mural. Today, we might say putting Leonardo in this position was pretty machiavellian. Which is ironic, because it was arranged with the help of none other than the inventor of machiavellianism, the council’s secretary, Niccolò Machiavelli.

Once word of this painting battle traveled outside Florence, young artists traveled to Florence to witness it. One of those artists: Raphael – armed with a letter of recommendation from the mother of the future Duke of Urbino to the leader of the Florentine Republic, stating that the twenty-one year-old was “greatly gifted…sensible and well-mannered.” It’s during this “Florence period” that Raphael’s work changed dramatically. It started to look as if he might know a thing or two about anatomy, he started aping Leonardo’s smokey sfumato technique, and drawing contorted, muscular men in the heat of battle. He learned a bit watching Michelangelo, but he learned a lot watching Leonardo.

Peter Paul Ruben’s sketch of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari (The original has been lost.)

A quick study of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, by Raphael

As it turned out, neither Leonardo nor Michelangelo finished his mural. For Michelangelo, it wasn’t a big deal. He got summoned to Rome, where he eventually painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Leonardo, however, had more of his career behind him than ahead of him. Yet another public failure meant he never got another public commission. So while Leonardo, in his sixties, was wandering around Europe, chasing what work he could, Raphael, in his early thirties, was getting showered with high-paying papal commissions, as a more-reliable Leonardo.

The rise and fall of Raphael

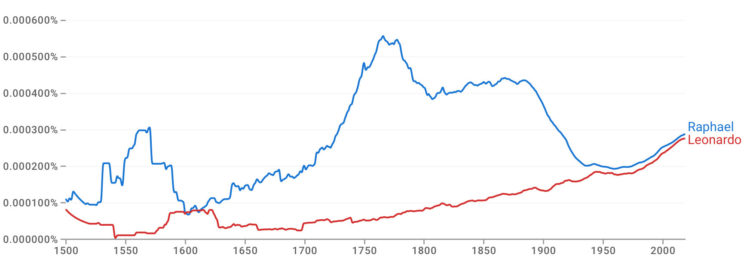

These days, we admire Leonardo more than we do Raphael, but that wasn’t always the case. That Raphael is one of the few people entombed in the palace of the gods, alongside kings, is testament to his popularity when he died. Heck, at his funeral, the pope kissed his hand. Around 1800, the church in which Leonardo was buried was destroyed in the French Revolution. Nobody bothered to try to recover Leonardo’s remains. They were mixed in with everyone else’s and forgotten.

Meanwhile, Raphael was as popular as ever. If you take a peek at Google Ngram, you see a sharp increase in mentions of Raphael around that time. For hundreds of years after Raphael’s death, he was considered the quintessential painter of the High Renaissance. The art academies around Europe, who controlled the opinion of what was or wasn’t good art, built their curricula around studying the work of Raphael. But as the influence of art academies crumbled in the late 1800s with the rise of Impressionism, so too did crumble the reverence for Raphael.

Meanwhile, Leonardo has risen in popularity over the centuries. Today, if you want to find a good book on Leonardo, you have lots of choices. Raphael, not so much. The probable cause of this rise in popularity and the probable cause of Leonardo’s struggles with follow-through are one in the same: Nature had more reason to fear Leonardo than Raphael.

Leonardo’s massive iceberg

Through the centuries after Leonardo’s death, his notes began to resurface. They had been inherited by someone who was supposed to compile and publish them, but were so numerous and disorganized, that was a nearly impossible task. His notes ended up collated and bound into individual notebooks, scattered amongst collectors around Europe. One notebook was found as recently as the 1960s, hiding in plain sight in Madrid, in the collection of the library.

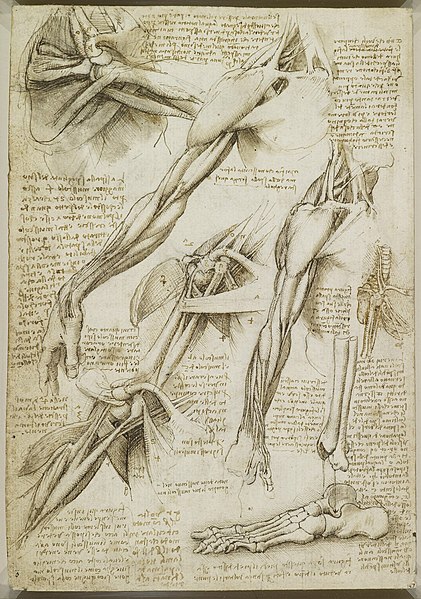

These notebooks have revealed that for Leonardo, painting a picture was about much more than painting a picture. When Raphael did an anatomy study, it was all about knowing how the skin on the surface of the body was shaped by the muscles underneath. The only purpose was to mimic Nature, on a superficial level. For Leonardo, an anatomy study was about much more. He didn’t just want to know what muscles were under the skin. He wanted to also know which muscles were engaged by which movements, or which nerves activated by which emotions. As a painter, there was no reason for Leonardo to know what the human heart looked like, or how it worked. Yet Leonardo made observations about the heart that would have advanced science by centuries, had they been published.

Leonardo searched, Raphael found

As I talked about on episodes 105 and 288, economist David Galenson would say Raphael was a conceptual innovator, while Leonardo was an experimental one. To Leonardo, there was no such thing as irrelevant information. In the course of researching how to paint something, he might make a new discovery about anatomy, metallurgy, geology, or some other field, that would set him down a different path. The art historian Eugene Garin thought, based upon Leonardo’s many thousands of pages of notes, that he was trying to compile a treatise of all human knowledge. Leonardo wasn’t studying Nature just so he could paint it convincingly – he was trying to understand all of Nature.

Raphael didn’t have to explore all aspects of the world. He merely had to copy the result of Leonardo’s thinking. Galenson told me, “It’s what conceptual innovators do, it turns out.” Conceptual innovators take an idea, and make it their own. It’s what Picasso did with the work of Cézanne, what Warhol did with the work of Pollack, what Hemingway did with the work of Stein and Twain.

The projects Leonardo pursued were impossible to finish

Leonardo’s experimental approach meant his paintings were never finished. He was always discovering something new, so he was constantly revising. For example, after one of his anatomy studies, he realized he had painted some neck muscles wrong, so he went back and repainted them thirty years after the fact. He did the bulk of his work on the Mona Lisa during four years, but moved it around for fifteen, making finishing touches until a paralyzed hand rendered him unable. The patron never got their painting, Leonardo never collected payment, and the Mona Lisa was still collecting dust in his studio when he died.

This experimental, iterative approach extended to Leonardo’s materials and methods, and made it even more difficult for him to follow through. The best-practice method of painting murals in fresco required laying down plaster and painting on it before it dried and literally set itself in stone. It wasn’t great for Leonardo’s blurry-edged painting style, and it made iteration impossible. He couldn’t lay down dozens of layers of paint over the course of years, as he did with the Mona Lisa. By the time Leonardo was painting his battle scene in the Florence Council Hall, his famous Last Supper was already fading and flaking, thanks to his resistance to painting in the reliable fresco technique. Not satisfied with adapting his style to this technique, Leonardo instead experimented once again on his battle-scene mural. He was almost finished, before the fire he was using to set colors got too close, destroying his work.

This Raphael world is nothing without Leonardos

Historically, the world rewards Raphaels. It rewards the ability to formulate a plan, follow through, collect payment and prestige, and move on. So, the world trains us to be Raphaels. Why do we follow a curriculum and fill out bubbles on standardized tests with #2 pencils? Because our teacher already knows the answer. They know the answer so well, they’ve programmed a computer to grade the test, and it’ll get confused if you use a #3 pencil.

But for the curriculum to be designed to make Raphaels, we first need Leonardos. We need people who explore and experiment. We need them to ask questions that might not have answers, and to come up with new questions nobody ever thought of. That’s not a straightforward process. It’s messy and disorganized, and it would cause any Raphael to pull their hair out. When you don’t always find answers, and the answers you do find lead to new questions, you don’t always finish.

The days of the Raphaels of the world are numbered. If somebody already knows the process, already knows the answer, we don’t need Raphael. A computer or machine can follow a process. Raphael knew this. Once his fame was established, he milked it for all it was worth. His later frescoes were painted by his staff of assistants in the largest workshop of the High Renaissance. He licensed his drawings to a printmaker, who sold copies of his work.

As it becomes harder to make it as a Raphael, it’s becoming easier to make it as a Leonardo. I think Leonardo would have been a great blogger. He wouldn’t have to collect and document all knowledge, then rely on an heir to collate, typeset, and publish his life’s work on expensive parchment. He could instead write and publish one note at a time, gradually building his treatise of human knowledge. He wouldn’t have to wander around Europe looking for patrons – he could get them without leaving his home.

If you’re a Leonardo, don’t bother being a Raphael

If you’re a Leonardo mind, don’t fall into the trap of evaluating yourself by the standards of the Raphael world. There’s a reason why the Raphaels are so good at getting it done: Their task is simpler. Don’t beat yourself up by your inability to plan and carry out a vision no one could reasonably execute on their first attempt. Instead, find a way to explore in public, one little project at a time, building up into your grand masterpiece.

Leonardo’s remains were forgotten for sixty years. Some scientist, perhaps motivated by the gradual resurfacing of the notes revealing Leonardo’s genius, gathered together some bones he figured were those of the master. They’re in a tomb in a chapel on the grounds of the chateau, and it’s one of the top attractions in Amboise. Are they actually Leonardo’s bones? Probably not. His remains are probably where they should be – not sealed away in some sarcophagus, but one with Nature.

Thank you for having me on your podcasts!

Thank you to Costa Michailidis for having me on the InnovationBound podcast.

As always, you can find interviews of me on my interviews page.

Join the Patreon for (new) bonus content!

I've been adding lots of new content to Patreon. Join the Patreon »

Subscribe to Love Your Work

Listen to the Podcast

- Listen in iTunes >>

- Download as an MP3 by right-clicking here and choosing “save as.”

- RSS feed for Love Your Work

Theme music: Dorena “At Sea”, from the album About Everything And More. By Arrangement with Deep Elm Records. Listen on Spotify »